The call came during a quarterly review. A sterile, automated voice.

“This is a message for the family of Eleanor Vance.”

My world went silent. The numbers on the projection screen blurred into nothing.

My brother, Mark, was two floors down, probably closing a deal. He got the same automated call.

We met in the parking lot of the “Evergreen Villa Care Home.” A name too cheerful for a place that smelled of bleach and quiet desperation.

“I can’t believe it,” Mark said, but his eyes were on his watch. He had a flight to catch at six.

And that’s the truth of it, isn’t it? We were sad. But we were also busy.

The facility director gave us a single cardboard box for her things. She said our mother was a “pleasure to have.” That she never complained.

That phrase should have been a warning siren. Instead, it just felt… convenient.

We took the key to her room. 3B.

The thing is, we’d only been inside a handful of times. Christmas, her birthday, the day we moved her in. We sent money. We called on holidays.

We told ourselves that was enough.

The room was neat. Impersonally so. A single bed, a nightstand, a worn armchair facing a window that overlooked a brick wall.

It looked less like a home and more like a storage unit for a person.

Mark started on the small closet, folding her two sweaters and a handful of blouses. I went to the nightstand.

There wasn’t much. A dog-eared novel. A pair of reading glasses. A tube of hand lotion.

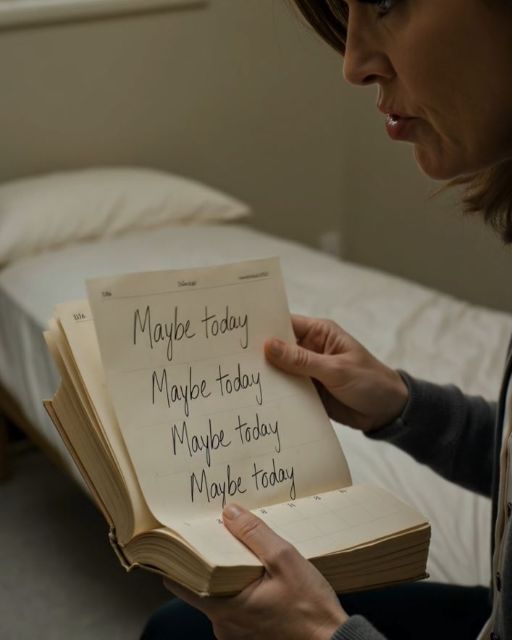

And a calendar.

One of those cheap, page-a-day desk calendars.

I picked it up. The date was yesterday’s. But she had written something on it. Two words.

My curiosity got the better of me. I flipped back a day. The same two words.

I flipped back a week. A month. A year.

Every single page for the last 842 days had the same two words written in her elegant, weakening script.

“Maybe today.”

The phrase repeated over and over, a silent scream on paper. A tally of every sunrise that brought a new hope of a visit. A hope that we extinguished with our silence.

My breath hitched. My stomach twisted into a cold, hard knot.

Mark stopped what he was doing and looked over. He saw the calendar in my hands, saw the look on my face. He didn’t need to ask.

But that wasn’t the part that broke me.

I flipped to the last page. Yesterday. The final entry she ever made.

The handwriting was a faint, spidery scrawl. It wasn’t the same two words.

It was just one.

“Enough.”

The word hung in the sterile air of the room, heavier than any sound could ever be. It was a verdict. A final, heartbreaking judgment on us.

Mark took the calendar from my trembling hands. He flipped through the pages himself, his usual confidence cracking with each turn.

“Oh, Mom,” he whispered, a sound so raw and broken it didn’t seem like it could come from my polished, always-in-control older brother.

He sank onto the edge of her perfectly made bed, the cheap calendar held like a sacred text.

I felt a wave of nausea. We were awful. We were just awful children.

We had outsourced her care, her comfort, her final years, and convinced ourselves that our financial contributions were a substitute for our presence.

The cardboard box on the floor seemed to mock us. A life distilled into a few cubic feet.

I knelt beside it, needing something to do with my hands. I pulled out a faded photo album.

There we were. Two gap-toothed kids in a park, our mother’s arms wrapped around us. She was radiant, her smile lighting up the cheap, glossy paper.

Another photo. Our high school graduations. She was standing between us, beaming with pride. She’d worked two jobs to make sure we had everything we needed for college.

We had forgotten that woman. Or maybe we hadn’t forgotten. Maybe we had just… filed her away.

Mark finally put the calendar down. He stared at the brick wall outside the window.

“The flight,” he said, his voice hollow. “I should call the airline.”

He didn’t move.

I continued sorting through the box. There was a small, worn wooden box inside. It smelled faintly of cedar.

I opened it. Inside, nestled on a bed of faded velvet, were dozens of small, handmade cards.

They weren’t for us.

I picked one up. It was made from simple construction paper, with a pressed flower glued to the front.

Inside, in our mother’s familiar cursive, it read, “For Sarah. On the birth of her first great-grandchild. May he bring you as much joy as your stories of him bring us. With love, Eleanor.”

I pulled out another. “For Mr. Henderson. I heard you were feeling down. Remember that spring always follows winter. Your friend, Eleanor.”

There were dozens of them. Birthday cards. Get well soon cards. Cards of simple encouragement.

None of them were for her family. They were for the other residents of Evergreen Villa.

Mark came over and looked over my shoulder. He picked up a card with a clumsily drawn picture of a cat.

“To Mrs. Gable. I hope Patches is chasing mice in a better place. He was a good boy. Thinking of you, Eleanor.”

We stood there in silence, reading through the small testaments of our mother’s kindness to a community we never even knew she had.

She wasn’t just waiting by the window. She was living.

“There’s more,” I said, my voice thick. Under the cards was a stack of papers, tied with a simple piece of yarn.

It was a manuscript. Or, it looked like one.

The title page read: “The Voices of Evergreen. Stories collected by Eleanor Vance.”

I untied the yarn. The first page was a short introduction.

“We all have a story,” she wrote. “Sometimes, when the world gets quiet, we forget that anyone wants to hear it. These are the stories of my friends. My neighbors. My family here. They deserve to be heard.”

I read the first entry aloud. It was the story of a man named Arthur, a former pilot who had flown missions in the war. He spoke of the skies over Europe, of fear and camaraderie.

My mother had captured his voice perfectly. His gruff humor, his moments of quiet sorrow. It was beautiful.

We kept reading. The story of a woman who had been a dancer in a traveling show. A man who had owned a bakery for fifty years. A retired teacher who still dreamed of her students.

These were the people we walked past in the hallways on our rare visits, the faces we barely registered. To our mother, they were an entire universe.

A soft knock came at the door. A young woman in scrubs stood there, her expression gentle.

“I’m so sorry for your loss,” she said quietly. “My name is Sofia. I was one of your mother’s aides.”

“Thank you,” Mark managed to say.

Sofia’s eyes fell to the manuscript in my hands. A small, sad smile touched her lips.

“Ah,” she said. “You found her book.”

“We didn’t know,” I said, feeling that familiar sting of shame. “We didn’t know she was doing this.”

“Oh, it was her whole world,” Sofia replied, stepping into the room. “She started it about two years ago. Said she was tired of waiting.”

My heart seized on that word. Waiting.

“She told me, ‘My kids are busy. I can’t just sit here waiting for a phone call. I have to do something.’”

Sofia walked over to the armchair by the window. “This was her office. She’d sit here with her little notebook and just listen. People would line up to talk to her.”

“She called them her ‘storytelling sessions.’ She made everyone feel like the most important person in the world.”

The calendar sat on the nightstand, a silent accuser. “Maybe today.”

Sofia seemed to follow my gaze. “That calendar,” she said softly. “I asked her about it once.”

She paused, as if deciding whether to share.

“She told me it wasn’t just about you two,” Sofia continued, her voice kind. “At first, maybe it was. But then it changed.”

“It became her little prayer for the day. ‘Maybe today I’ll get Arthur to talk about his wife.’ ‘Maybe today I’ll finish Sarah’s story.’ ‘Maybe today I’ll find the right words for Mr. Henderson’s card.’”

The 842 pages of hope weren’t just for us. They were for everyone. They were for her newfound purpose.

The weight in my chest shifted, not lessening, but changing from the sharp pain of guilt to a dull, profound ache of awe.

“And yesterday?” I had to ask, my voice barely a whisper. “The last word. ‘Enough.’”

Sofia’s eyes welled up with tears. She nodded slowly.

“Yesterday afternoon, she finished the last story. It was for a woman on the fourth floor who passed away last week. Your mom wrote it from the memories the family shared with her.”

“She typed up the final page, put the whole manuscript together, and tied it with that yarn. She held it in her lap for the longest time, just looking at it.”

Sofia’s voice cracked. “She looked up at me and she smiled. The most peaceful smile I’ve ever seen.”

“She said, ‘It’s done, Sofia. It’s enough.’ And then she squeezed my hand.”

“She passed in her sleep a few hours later. The doctor said her heart just… stopped. It was peaceful.”

Enough.

It wasn’t a cry of despair. It wasn’t a final, bitter sign-off.

It was a declaration of completion. Of a job well done. Of a life that had found its meaning, right here in a room with a view of a brick wall.

She had finished her work. She was ready.

The silence that followed was different. It wasn’t empty anymore. It was filled with the presence of a woman we were only just getting to know.

Mark cleared his throat. He picked up his phone, but he didn’t check his emails. He cancelled his flight.

“We should get this published,” he said, his voice firm with a new kind of purpose. “All of these stories.”

I looked at him. Really looked at him. The deal-maker, the man with the schedule, was gone. In his place was just my brother. Eleanor’s son.

“Yeah,” I said. “We should.”

We spent the rest of the afternoon in that small room, not packing, but reading. We read about heroes and lovers, bakers and dancers. We laughed at their jokes and we cried for their losses.

We learned more about our mother in those few hours than we had in the past twenty years. We learned about her patience, her empathy, her incredible ability to see the light in people that the world had forgotten.

We found her legacy not in a will or a bank account, but in a stack of papers tied with yarn.

A few months later, we held the first published copy of “The Voices of Evergreen.” We threw a party at the care home. All the residents whose stories were in the book were the guests of honor.

We used the book’s proceeds to build a small library and a dedicated “storytelling room” in the facility, named “The Eleanor Vance Wing.”

Mark and I are different now. We talk more. Not about work or schedules, but about things that matter. We visit the home often, not out of guilt, but because it feels like coming home.

We listen to the stories.

I still have that page-a-day calendar. It sits on my desk. I don’t look at the past pages filled with her handwriting.

I only look at the final one.

“Enough.”

It’s a reminder that a life well-lived isn’t measured by what you accumulate or who comes to see you. It’s measured by what you give.

It’s a reminder that it’s never too late to find your purpose. And that sometimes, the most profound love is found not in waiting for others, but in building a world of your own, right where you are.

It was, in the end, more than enough.